Fear is a powerful emotion that has profoundly influenced human evolution, cognition, and culture. It has been a catalyst for survival, a foundation for keeping social order whether a part of religion or politics, and a wellspring of myths involving spirits and the occult. While fear can protect us from immediate dangers and act as an effective deterrent, it has also spurred byrpoducts in the form of abstract symbolic thinking, making various mental scenarios for virtually every situation and by proxy rituals that connect societies. However, how strong can this deterrent be? Can it become so engrained that it in fact paralyses us, forbidding us from challenging the status quo, and artificially cocooning ourselves in perceived safehavens, whether they are the embrace of cults, political groups, toxic relationships or unhealthy processes in general. So what role does fear play in civilisational resilience?

The Evolutionary Roots of Fear and Religion 🧬

Understanding fear’s impact requires examining its evolutionary origins and how it spurred the development of symbolic thinking and, by extent, social constructs that cater for these cognitive processes like politics or religion (two obvious structures that evolutionarily hack our brains in order to achieve scalable social behaviour, steered often by fear and threats). But let’s get back to evolution. Anticipating danger (for example, a predator or someone in your social group that could be a threat) not only enhanced survival but also fostered complex cognitive abilities. 🧠 Fear’s role in evolution extends beyond immediate survival; it has shaped our cognitive abilities and social structures, and by fostering symbolic thinking and religious practices, fear has been instrumental in the development of complex human societies. So let’s break it down!

Fear as a Catalyst for Symbolic Thinking

Fear isn’t solely a reactive emotion; it’s anticipatory. Early humans needed to predict potential threats, contributing to the development of symbolic thinking—the ability to represent abstract concepts and imagine future scenarios (Mithen, 1996). This cognitive leap allowed, amongst other things, humans to create tools, plan hunts, and develop social strategies.

Hyperactive Agency Detection Device (HADD)

Evolutionary psychologists propose that humans evolved a Hyperactive Agency Detection Device (HADD), predisposing us to attribute agency to ambiguous stimuli (Barrett, 2000). For instance, interpreting rustling leaves as a predator rather than the wind increased survival chances. This bias toward assuming intentional agents laid the groundwork for belief in spirits and deities - this is closely connected with the paragraph above and the effect on social dynamics and structures it has. Fear of the unknown and the need to explain natural phenomena may have given rise to religious beliefs. By attributing unexplained events to supernatural agents, early humans reduced anxiety and fostered group cohesion (Boyer, 2001).

Rituals as Anxiety-Reducing Mechanisms

Religious rituals often alleviate fear and uncertainty. Performing rituals provides a sense of control over uncontrollable events like weather or disease. This collective behavior reinforces social bonds and shared beliefs, advantageous for group survival (Malinowski, 1948).

The Neurobiology of Fear

The amygdala, a small, almond-shaped structure in the brain’s limbic system, plays a pivotal role in processing fear (LeDoux, 2012). When a potential threat is perceived, the amygdala triggers the hypothalamus to initiate the “fight, flight, or freeze” response. This leads to the release of stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol, preparing the body to react swiftly.

Preparedness Theory

Psychologist Martin Seligman’s Preparedness Theory posits that humans are biologically predisposed to fear certain stimuli that posed threats to our ancestors, such as snakes, spiders, and heights (Seligman, 1971). This explains why certain phobias are more common and can be more easily acquired than others.

Fear Conditioning

Studies like Watson and Rayner’s Little Albert experiment demonstrated how fear could be learned through classical conditioning (Watson & Rayner, 1920). This learning mechanism allowed early humans to associate certain cues with danger, enhancing survival by avoiding harmful situations.

Social Evolution of Fear

As human societies evolved, so did the nature of fear. Social fears—such as fear of ostracism or social rejection—became significant because being part of a group was crucial for survival. These fears helped enforce social norms and cooperation, which were essential for group cohesion and success.

Historical and Archaeological Examples of Ghosts and Occultism 👻

You know me by this point - I LOOOOOVE history and archaeology. So let’s have a look at how our ancestor homebois dealt with fear and terror. Throughout history, humans have believed in and interacted with the spirit world. So let’s explore various cultures’ dealings with ghosts, spirits, and the occult, all while highlighting associated rituals - because now we know how evolutionarily important those are!

Ancient Mesopotamia

In ancient Mesopotamia, ghosts (etemmū) were spirits of the deceased who could influence the living (Bottéro, 2001). People performed rituals and offered food and drink to appease them. The “Epic of Gilgamesh” includes encounters with spirits, reflecting concerns about death and the afterlife.

Egyptian Book of the Dead

The Egyptians developed an extensive belief system around the afterlife. The Book of the Dead is a collection of spells intended to guide the deceased through the underworld and protect them from evil spirits (Assmann, 2005). Mummification and tomb inscriptions were rituals to ensure safe passage and prevent the dead from haunting the living.

Chinese Ancestral Worship and Ghost Festivals

In China, ancestor worship has been a longstanding tradition. The Ghost Festival (Yu Lan) honors ancestors and wandering spirits (Thompson, 1988). Rituals include offering food, burning incense, and paper replicas of valuables. These practices reflect beliefs in the spirits’ influence on the living and aim to prevent misfortune.

Neolithic Burial Practices

Neolithic societies showed complex burial customs. At Çatalhöyük in Turkey, the dead were buried beneath homes, and skulls were sometimes removed and plastered, possibly for ancestor veneration or protection against the dead (Hodder, 2006). These practices indicate early attempts to understand and mitigate fears surrounding death.

Madagascar’s Famadihana

💃 In Madagascar, Famadihana, or “turning of the bones,” is a ritual where families exhume ancestors’ remains, rewrap them, and celebrate with music and dance (Bloch, 1971). This practice strengthens family bonds and transforms fear of death into celebration.

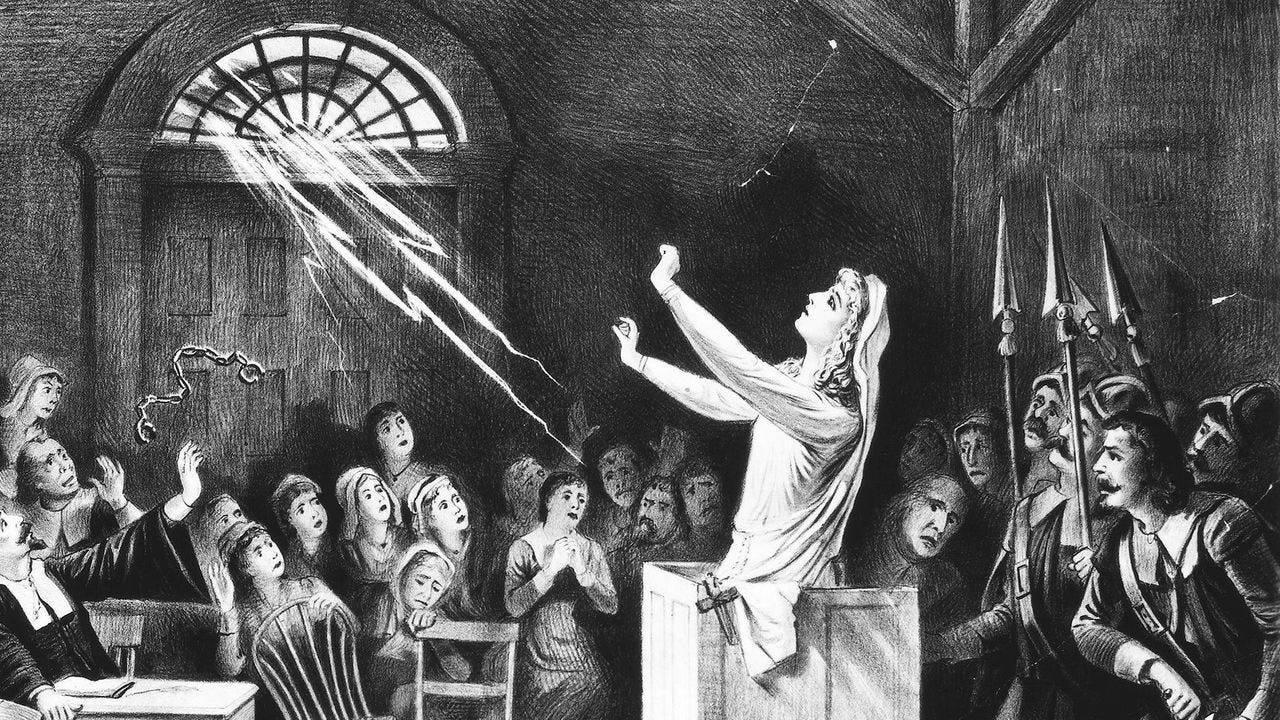

European Occultism and Witch Trials

During the Middle Ages, Europe saw a surge in occult practices and fear of witchcraft. The Malleus Maleficarum, published in 1487, was a treatise that fueled witch hunts (Kramer & Sprenger, 1487). Rituals to ward off evil spirits became common, and fear of the occult led to social paranoia.

Fearsome Figures and Rituals Across Cultures 👹

Mythical creatures and deities often embody collective fears and moral lessons. So how do societies personify fear and the rituals associated with these entities? And does it allow cultures to navigate uncertainties? These entities can often serve as moral compasses, reinforcing societal values and norms through associated rituals - so let’s have a look at some of these creepy stories.

The Djinn in Middle Eastern Folklore

In Islamic tradition, Djinn are supernatural beings made of smokeless fire (El-Zein, 2009). They can influence humans, sometimes malevolently. Rituals to protect against Djinn include reciting Quranic verses and using amulets, reflecting fears of the unseen and the need for divine protection.

The Maori’s Taniwha

In Maori mythology, Taniwha are water-dwelling spirits that can be guardians or dangerous creatures (Orbell, 1998). Communities perform rituals to honor them, ensuring safe passage through their territories. These beliefs embody respect for nature’s power and fear of natural dangers.

Vodou Spirits in Haiti

🕯️ Vodou incorporates a pantheon of spirits called Lwa, who interact with the living through possession during rituals (Desmangles, 1992). Ceremonies involve drumming, dancing, and offerings. While some Lwa are benevolent, others are feared. These practices address fears of misfortune and seek guidance.

Aztec Deities and Rituals

The Aztecs performed rituals involving human sacrifice to appease gods like Huitzilopochtli, believing it ensured the sun would rise (López Austin, 1988). These practices were rooted in fear of cosmic catastrophe and maintained societal order.

Fear in Fairy Tales and Literature 📖

Fear has been central in storytelling, used to convey lessons and reflect societal anxieties. Often, these phenomena (like gothic horror and the industrial revolution/elicrtification of society) accompany social upheavalas and changes. Through storytelling, fear becomes a tool for reflection and education (and how that mechanism works, go have a look at our Fairytales blog. Literature allows societies to confront and process anxieties, offering insights into the human condition.

Grimms’ Fairy Tales

The Brothers Grimm collected and published tales that often contained dark themes and frightening elements (Zipes, 2006). Stories like “Hansel and Gretel” deal with abandonment and cannibalism, reflecting fears of famine and parental neglect. “Snow White” explores jealousy and the fear of betrayal. These tales used fear to impart moral lessons and prepare children for the harsh realities of life.

Horror Literature

Authors like Edgar Allan Poe delved into psychological horror, exploring fears of madness, death, and the unknown. Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein” addresses fears of playing God and the unintended consequences of unchecked scientific pursuit (Shelley, 1818). H.P. Lovecraft’s works tap into cosmic horror, evoking a fear of the incomprehensible vastness of the universe. Lovecraft himself was a problematic fellow, with some deep racist thoughts, but his genre of cosmic horror reflects the social and economic upheaval post-WW1 in the US.

Modern Cinema and Horror Films

🎬 Horror films continue to reflect and process societal fears. Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho” taps into fears of mental illness and hidden identities. “The Exorcist” confronts fears of demonic possession and loss of control. Jordan Peele’s “Get Out” brings racial tensions and systemic oppression to the forefront (Pinedo, 1997). These films allow audiences to confront fears in a controlled environment, offering catharsis and insight.

Folklore of Baba Yaga

In Slavic folklore, Baba Yaga is a witch living in a hut on chicken legs (Johns, 2004). She tests protagonists’ bravery, addressing fears of the wild and the unpredictable nature of life.

The Banshee in Irish Folklore

The Banshee is a female spirit whose mournful wailing foretells the imminent death of a family member (MacKillop, 2004). Representing the inescapability of death, the Banshee embodies fears of loss and the supernatural, reminding communities of life’s fragility.

Japan’s Yōkai and Oni

Japanese folklore is rich with Yōkai (supernatural beings) and Oni (demons). Creatures like the Kappa, a river monster, warn of the dangers lurking in nature, while the Tengu serves as a caution against arrogance (Foster, 2009). These stories personify natural and moral fears, teaching respect and humility.

The Wendigo in Native American Legends

In Algonquian legends, the Wendigo is a malevolent spirit associated with cannibalism and insatiable greed, especially during harsh winters (Johnston, 1990). It symbolizes the fear of societal breakdown and the loss of humanity due to extreme conditions or moral corruption.

Anansi the Spider from West Africa

🕷️ Anansi is a trickster deity in Akan folklore, known for his cunning and ability to outsmart others (Rattray, 1930). While not overtly fearsome, Anansi’s tales often highlight the consequences of deceit and greed, instilling moral lessons through stories that play on the fear of social repercussions.

Fear in Political Discourse 🏛️

Fear is a potent force in politics, capable of uniting or dividing societies; fear has been used historically and in contemporary times to influence political agendas and public perception. While fear can mobilize societies against genuine threats, it can also be exploited to manipulate and control and recognizing the use of fear in political discourse is crucial for protecting individual rights and building healthy civilisational resilience and a critical understanding of governance structures.

Historical Uses of Fear in Politics

• The Red Scare: During the early Cold War era, fear of communism in the United States led to McCarthyism, where accusations without proper evidence ruined careers and lives (Schrecker, 1998). This period reflects how fear can be manipulated to suppress dissent and control the populace.

• Salem Witch Trials: In 17th-century New England, mass hysteria and fear of witchcraft resulted in the execution of innocent people (Karlsen, 1987) and illustrates how fear can override rationality and justice.

Fear-Mongering and Propaganda

Governments have often used fear to justify policies or actions. Nazi Germany utilized propaganda to instill fear and hatred towards Jews and other minorities, leading to widespread persecution (Koonz, 2003). By creating an “us versus them” mentality, leaders can manipulate public sentiment to support their agendas - and happens every day from both the left and right side of the political spectrum, and is evidenced by unhealthy tribalisation online when it comes to social media. We’ll have a blog coming on politics soon.

The War on Terror - the name’s literally on the tin with this one

Following the September 11 attacks, fear of terrorism reshaped international policies and civil liberties. Measures like the USA PATRIOT Act expanded government surveillance, raising concerns about privacy and human rights (Mueller, 2006). Of course, this is a hugely sensitive subject, but if we approach it from an evolutionary perspective, we can see how language, symbolism, narratives can shape wars even on abstract intangible concepts like ‘terror’, which is an interesting footnote for a blog about fear.

Fear in Relationships ❤️

Fear significantly impacts personal relationships, affecting how we connect and interact with others. Fear in relationships often stems from deep-seated insecurities or past experiences and by confronting as well as recognising these fears (which often bleed into professional life as well), individuals can improve their emotional well-being and build stronger, more fulfilling connections - while this is of course a much more poignant topic for therapy, this level of fear (and not just the systemic, social manifestations) is important to mention.

Vulnerability

Dr. Brené Brown emphasizes that vulnerability is essential for authentic connections, but fear of being hurt often prevents people from opening up (Brown, 2012) and this fear which I’m sure a lot of the readers can associate with can lead to emotional barriers, inhibiting intimacy and mutual understanding.

Attachment Styles

Attachment theory suggests that early interactions with caregivers shape our patterns of attachment and fears in relationships (Bowlby, 1988). Anxious attachment can result in fear of abandonment, while avoidant attachment may stem from fear of dependency or being overwhelmed. These are very powerful mechanisms, which, more than Baba Yaga or the Wendigo can really paralyse an individual and prevent them from flourishing and finding happiness. Unfortunately, fear and its evolution has many unpleasant byproducts such as this, BUT nothing we can’t handle as humans without a little understanding of the problematic.

The Double-Edged Sword of Fear ⚔️

As we can see, fear’s dual nature means it can protect us but also hold us back. So how to balance it out, and approach this complex phenomenon?

Evolutionary Benefits

• Survival Mechanism: Fear prompts immediate responses to danger, enhancing survival.

• Learning Tool: Associating negative experiences with fear teaches us to avoid harmful situations (Öhman, 2008).

• Social Cohesion: Shared fears can strengthen group identity and cooperation.

Paralysis and Stagnation

However, fear can also be detrimental:

• Inhibiting Innovation: Fear of failure or the unknown may prevent individuals and societies from pursuing new ideas or embracing change.

• Mental Health Issues: Excessive fear can lead to anxiety disorders, phobias, and stress-related illnesses (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

• Resistance to Change: Fear can make people cling to familiar ways, hindering adaptation and progress.

Overcoming Fear for Effective Problem-Solving

🚀 Addressing fear is crucial for personal and societal advancement. Techniques such as cognitive-behavioral therapy help individuals challenge and reframe irrational fears (Hofmann et al., 2012). Cultivating a growth mindset encourages viewing failures as learning opportunities (Dweck, 2006). Societies that promote education, open dialogue, and critical thinking are better equipped to overcome fear-based paralysis. By recognizing when fear is protective and when it is limiting, we can leverage its benefits while mitigating its drawbacks. Overcoming unnecessary fears is essential for innovation, creativity, and solving complex problems. As we can see and have explored together, fear is an intrinsic part of the human condition, influencing our evolution, cultures, stories, politics, and relationships. While it has been a crucial survival mechanism, it can also restrict us from exploring new ideas and embracing change. By understanding the multifaceted nature of fear, we can transform it from a paralyzing force into a motivating one. Also, seeing what’s behind the facade of fear and what lies in the unknown has been a basic human characteristic throughout our evolutionary track record - so in order to be individually and civilisationally resilient, let’s embrace, uncover fear and don’t let ourselves and our society be manipulated by scarecrows.

References 📚

• Assmann, J. (2005). Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt. Cornell University Press.

• Barrett, J. L. (2000). Exploring the natural foundations of religion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(1), 29-34.

• Bloch, M. (1971). Placing the Dead: Tombs, Ancestral Villages, and Kinship Organization in Madagascar. Seminar Press.

• Bottéro, J. (2001). Religion in Ancient Mesopotamia. University of Chicago Press.

• Boyer, P. (2001). Religion Explained: The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought. Basic Books.

• Desmangles, L. G. (1992). The Faces of the Gods: Vodou and Roman Catholicism in Haiti. University of North Carolina Press.

• El-Zein, A. (2009). Islam, Arabs, and the Intelligent World of the Jinn. Syracuse University Press.

• Hodder, I. (2006). The Leopard’s Tale: Revealing the Mysteries of Çatalhöyük. Thames & Hudson.

• Johns, A. (2004). Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. Peter Lang Publishing.

• Kramer, H., & Sprenger, J. (1487). Malleus Maleficarum.

• López Austin, A. (1988). The Human Body and Ideology: Concepts of the Ancient Nahuas. University of Utah Press.

• Lovecraft, H. P. (1927). The Call of Cthulhu. Weird Tales.

• Malinowski, B. (1948). Magic, Science and Religion and Other Essays. Free Press.

• Mithen, S. (1996). The Prehistory of the Mind: The Cognitive Origins of Art, Religion and Science. Thames & Hudson.

• Orbell, M. (1998). A Concise Encyclopedia of Māori Myth and Legend. Canterbury University Press.

• Shelley, M. (1818). Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. Lackington, Hughes, Harding, Mavor & Jones.

• Thompson, L. (1988). Chinese Religion: An Introduction. Wadsworth Publishing.